Part of storytelling is making sense of chaos…Dana A. Williams’ Life@ GWN

Part of storytelling is making sense of chaos…Dana A. Williams’ Life@ GWN

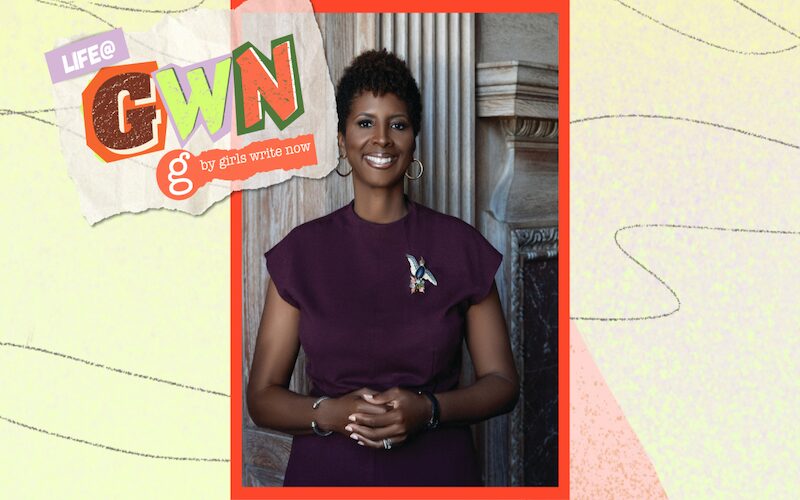

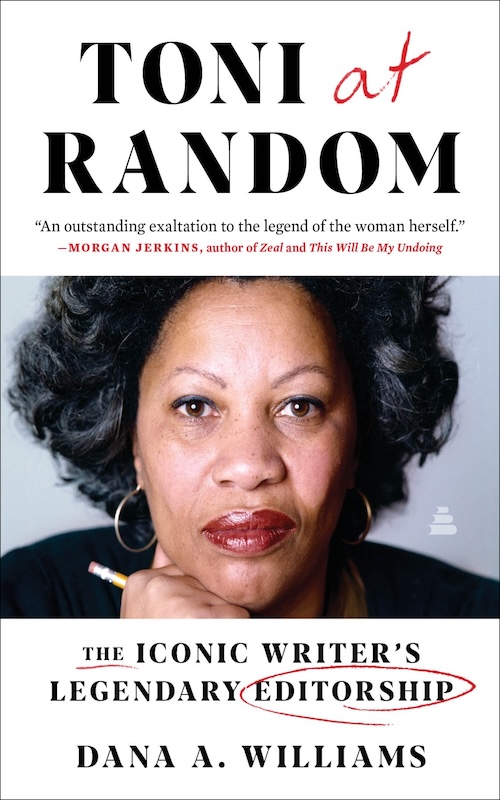

Dana A. Williams is not just a scholar; she’s a storyteller. Her CV boasts accolades from the Dean of Howard University Graduate School to this year’s Girls Write Now Honoree because she knows that the best way to get to the truth is to tell a story. And she learned from the best. With Toni Morrison as a personal and professional mentor, Dana built a deep understanding of storytelling as sense-making, self-making, and collective building. The best lessons are not taught, but learned, and in Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, Dana documents how Toni Morrison built community, identity, and legacy for Black literature.

In a conversation with fellow HBCU graduate and Girls Write Now Community Coordinator Annaya Baynes, Dana shares the moments of discovery, learning, and mentorship that honor and celebrate Toni Morrison’s legacy.

Professor Williams, would you like to introduce yourself?

Yes. Hi, Annaya. Hi, audience. I’m Dana Williams. I am professor of African American Literature and dean of the Graduate School at Howard. And most excitingly, right now, author of Toni at Random.

I’m so excited to talk to you about this book. I’m a Toni Morrison fan, and I’ll introduce myself as well. I’m Annaya Baynes, a community coordinator at Girls Write Now. I was a Girls Write Now mentee as well, and I’m also a graduate student at NYU in their Cinema Studies Department. I know you’re an HBCU alum too, Grambling State and Howard, so I have to say I am also an HBCU alumnus from Spelman. Would you like to go into your excerpt from Toni at Random?

This is from the first chapter, and it really sets up Morrison’s representation of her work as an editor. It’s from the Black Writers Conference at Howard, the second time they held the conference, and the first time with a panel on publishing. Toni Morrison enters the room, and there is some uncertainty about how the panel will go. Of course, in the room there are plenty of writers, and everyone is anxiously waiting for her. This passage picks up after she has given her remarks. For just over 45 minutes Morrison fielded questions alongside the other panelists until the question and answer period finally ended. Most of the concerns about publishing would be addressed with concrete action items during the business meeting. What Morrison made clear, even more insistently than the other panelists was: commitment and self-determination were the things in highest demand—commitment and self-determination. The obstacles were outsized, yes, but they were not insurmountable. Somewhere between exasperation and entreaty, she insisted to the audience: “While there may not be many stores that are stocking Black books, while there may not be many Black bookstores, while there may not be many places where editors can get reviews for their books, while there may not be many places on television, radio, and so on that will give us the opportunity to distribute or publicize our books—there is one thing, and there’s always been that one thing—that’s us. We’re all we got. And that’s the title of that chapter and it starts like this:

“Everything about Toni Morrison’s distinguished editorship pointed to her understanding of that one truth, that any attempt to revolutionize the publishing industry to be more inclusive of Black authors and Black stories would require an army of people united by a belief in literary and artistic excellence in Black culture, while once vibrant sociopolitical ties dissolved into gradual disconnection, and the loss of support networks through neglect and design translated into a loss of the kind of collective identity that had formed in the 1960s. Morrison never lost sight of the belief that Black people could be everything they needed. She knew she was not alone in that belief. She enlisted some of the highest and the brightest minds to join her, and they got to work trying to make a revolution. One book at a time, a revolution, one book at a time.”

I’d love to hear about your process for writing your latest book, Toni at Random. What was the path? Did it begin with the idea of just writing about Toni as an editor instead of as a writer?

While Toni Morrison is mostly known for her own authorial work, this book began with the intent to really focus on her work as an editor, but not exclusively. By that, I mean I was most interested in the fiction that she edited. I had taken this class that was actually using the books she edited by Leon Forrest, Henry Das, Gail Jones, Toni Cade Bambara, and Nettie Jones. We did do John McCluskey, but we didn’t do Wesley Brown. The Norton Anthology tells us about literature of 1970, and that’s actually the name of the period. Everything else has really specific names, but then there’s just “literature after 1970”. I got really interested in the editorship itself, and that was in part because of my first few interviews about the book with Toni Morrison. Although she knew I wanted to focus on the fiction, she talked about everything except the fiction, which meant, all right, she must be trying to tell me something! I didn’t know it then, but I was actually getting edited in real time—it was like, here is the things that you also have to include. So my writing process shifted as the focus of the book shifted. I moved outside of just thinking about the fiction writers to begin contextualizing them with the other books being published at the time. Those books expanded into thinking about what it means to be an editor, and what it meant in particular for Toni Morrison to be an editor at Random House at a crucial time right after the Black Arts Movement when she was emerging as a well-known author who would go on to become one of the most well-read, most frequently read authors of our time.

Thank you so much. That was really rich. You said you had some interviews with Toni Morrison as part of your research process for the book. What was it like writing about someone with whom you were also able to have a conversation? Were you thinking about how she would receive the book?

Yes. It was interesting to be able to talk to her about the project. It gave me confidence on both sides, confidence because I had the benefit of running things by her to say, this is what I think. Is this accurate? Or here’s a question that I have. Can you answer it? As an example, there were months and months, even years, of correspondence between her and fellow author and activist Toni Cade Bambara. And then the correspondence just stopped. And so I went to Emory, which is where Toni Bombara’s papers are, and I went to Columbia, where the Morrison editorial files are, and I didn’t see anything. When I asked her what happened, Toni said quite casually, “oh, she was staying with me at that time,” because by then Toni Bambara had moved to Atlanta to finish her book. It would often be the case that, if Morrison was under a strict deadline, people would stay with her and work non-stop for two weeks just to make sure that it was done. Even though it was heartbreaking for me as a researcher because a really great correspondence ended, I also had the great benefit of talking directly with Toni Morrison about it.

I really did try to write a book that she would have been proud of. I was disappointed that I didn’t finish before she made her transition, but I do think that she would have ultimately appreciated what the book came to be, in part because she influenced what the book came to be. I intended it to be much smaller, and she encouraged me to see it for the larger thing that it needed to be. I’m certainly not Toni Morrison, but I felt so inspired to write and dive into the depths of her words and the power of them.

How did Toni Morrison’s time at Random House impact your relationship to writing?

I think I had in the back of my mind the kinds of questions that she asked her authors. So as I was writing, I was thinking, all right, I’m being edited informally by Morrison based on what I know. She would have asked: What did it look like? What did it feel like? How did you experience it? What is its relation to the other thing that you’re talking about or that people are thinking about? This happened as I was writing about The Black Book, which is one of the books for which Morrison’s editorship is most known. People knew that she worked on The Black Book, and they knew she got the idea for Beloved from reading about Margaret Garner. I wanted to talk about why The Black Book was done and what it did well. It’s not a narrative book. It’s 99% visual, with no contextualization outside of epigraphs that begin different sections. So I needed to talk about what it meant to do a visual book and to put it in context with the Whole Earth Catalog, which in its representation of the whole Earth, had so very little engagement with Black life and Black culture in America or abroad. But it’s the whole earth, supposedly. So I wanted to contextualize it in that way. And then I also wanted to contextualize it as a representation of Black life that needed to be an event. I asked some of the questions I knew she would have asked had she been my editor, and I began to write for an audience that was broader, a more mass appeal if you will, a more commercial response.

In your book you say Morrison was interested in thinking about the ways fiction told stories history would not. So I’d like to ask, what is the importance of storytelling and shaping the world we want to live in?

Oh, it’s remarkably important, because stories help us make sense of things that don’t otherwise make sense. The great Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o would say it was only fiction that could help make sense of the howling winds of what was happening at times when he was imprisoned. It wasn’t drama, it wasn’t poetry, it was fiction. Part of storytelling is making sense of chaos or making sense of grief, making sense of anticipation. I think it’s important to have diverse voices—young Black voices, most especially for me, because there are questions that we don’t even know how to frame that can be answered by telling the story. Then we can figure out. There are answers that come through stories that we can’t otherwise relate to. You want to read stories by different people because people have different experiences. If we get people with different experiences telling those stories, we get to empathize and imagine differently. And that also connects, I believe, with your background as an academic, and a scholar, and an educator. I see those similar parallels with Toni Morrison and how much she valued education and her work with textbooks.

This year Girls Write Now published an anthology of mentee work titled Hope Lives in Our Words. The world feels particularly precarious right now. I don’t know if you’ve been feeling it. I’ve been feeling it every day. When you’re feeling overwhelmed by everything, what makes you feel hopeful?

Oh, man, you already know the answer to this one. I read, and sometimes I write after I read. But more than anything, I read because I’m trying to make sense of the world. And it’s not an escape. I need my brain to work, and my brain works when there are words on the page, which is why it’s so important for girls to write, why it’s so important for everyone to write, to be able to give voice to whatever the interior thing is that you’re trying to express. Even if you aren’t writing with pen and paper, even if you’re typing, or writing intellectually—if you’re writing the thoughts in your mind, you can make sense of them. I think that’s really important because the precarity is real. The uncertainty seems to be everywhere, but that is a tactic to make us feel unsettled, and to make us feel unstable. Books can bring us back to center, and that includes poetry. The one that resonates with me most often is Lucille Clifton’s won’t you celebrate with me? Every day, something’s trying to kill us. She’s talking specifically about breast cancer killing her, and she says: “wont you celebrate with me…that every day something has tried to kill me and has failed.” That’s worth celebrating.

Dana A. Williams is Professor of African American literature and Dean of the Graduate School at Howard University. She is…

Visit Profile